A deeper look at the symbols, silences, and the sister who couldn’t save him

The Archer Who Never Released

I keep coming back to this image.

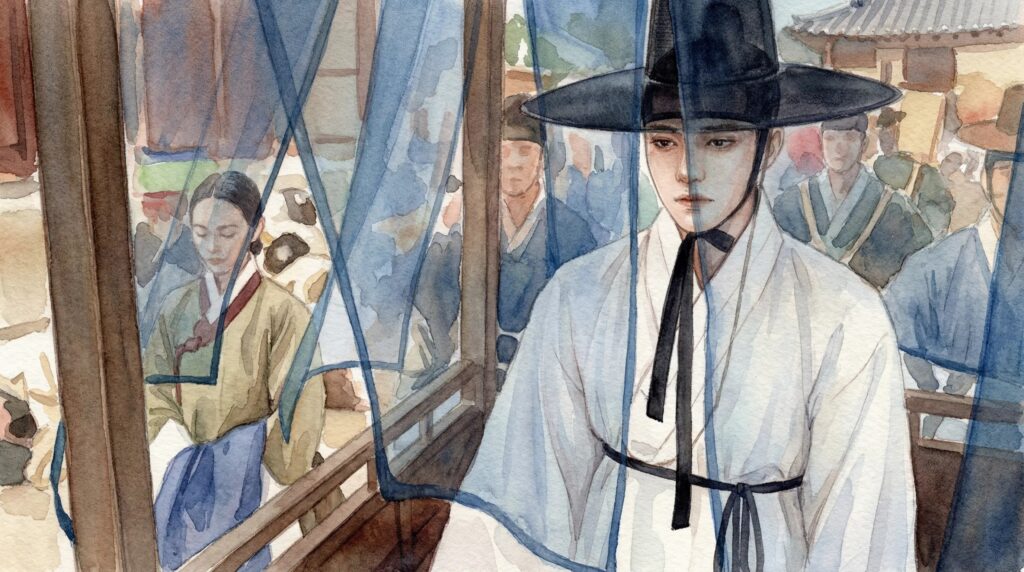

Park Ji-hoon, bow drawn, eyes locked forward. The poster for The King’s Warden (왕과 사는 남자) dropped on December 19th, 2025, and it’s been sitting with me ever since—not because of what it shows, but because of what it can’t show.

At the premiere, Director Jang Hang-jun said something that stopped me cold: “I didn’t want him portrayed as just helpless.”

And there it is. The Korean historical record has painted King Danjong (단종) in sorrow for 600 years—a boy king paralyzed by grief, drowning in circumstances beyond his control. We know him as Korea’s saddest king. We don’t know him as the archer.

But Park Ji-hoon trained in traditional Korean archery (gungung, 국궁) for this role. His archery master kept praising his form, saying it was beautiful. Not tragic. Not helpless. Beautiful.

That distinction matters.

Because when you’re 17 years old and you know exactly how your story ends, choosing to hold your posture steady—choosing to draw that bow with perfect form—that’s not passivity. That’s defiance.

17 Layers of Dignity, Zero Layers of Protection

Let’s talk about what he’s wearing in that poster, because every single layer tells a story.

The Gwanryongpo (곤룡포): The King’s Ceremonial Robe

That robe isn’t pure black. It’s closer to a deep, dark blue-green (검푸른색)—the kind of color that shifts in the light. And that golden dragon embroidered across the chest? Real gold thread. Only royalty could legally wear this symbol. If you were caught wearing it as a commoner, that was grounds for execution.

But here’s the paradox I can’t stop thinking about: the more symbols of power Danjong wears, the more trapped he becomes.

These aren’t protections. They’re markers. They’re targets.

The Layers on His Head: Sangtu, Manggeon, Donggot, Sangtugwan

Okay, this is where the costume team really showed their research.

From bottom to top:

- Sangtu (상투): The topknot that marked him as an adult male in Joseon society

- Manggeon (망건): The black headband holding the topknot in place

- Donggot (동곳): The pin piercing through the crown

- Sangtugwan (상투관): The square-shaped crown

- The royal hat (갓): And here’s where it gets interesting

If you watched Kingdom on Netflix, you’ve seen these hats. But the shape is actually different. Kingdom is set in the 1600s or later—the late Joseon period. By then, the hats had evolved to be taller and more angular.

But this film? 1457. Early Joseon.

So the hat is shorter, more rounded, with a wider base. The costume team literally researched 200 years of hat evolution to get this right.

From the donggot pin at the bottom to the royal hat at the top: 17 layers of dignity. Zero layers of protection.

The costume team knew this boy king wore every symbol perfectly. But symbols can’t stop a coup. They can’t stop your uncle. They can only hold your posture steady.

The Sister’s House: When Your Sanctuary Becomes the Crime Scene

Here’s the part that breaks me every time I think about it.

When Danjong’s father died and he became king at 12, he had no family left in the palace. So he would visit his sister’s home. A lot.

Princess Gyeonghye (경혜공주) lived close to the palace, in what’s now Bukchon (북촌). Her home became the only place where Danjong felt safe. Historical records actually document this:

“His Majesty feels comfortable staying at his brother-in-law’s home.”

Even court officials agreed: if it makes the boy king feel safe, let him stay there.

And his uncle Sejo (세조)? He knew this.

So that’s exactly where he struck.

October 10, 1453: The Night Everything Changed

Danjong was 13 years old, sleeping at his sister’s house, when Sejo’s soldiers came.

One by one, they executed Danjong’s supporters—ministers who had protected him—in or near that house. Some were killed in the courtyard. Some in the rooms where Danjong had laughed with his sister just hours before.

This is how you break someone without touching them.

You don’t just take away their power. You take away their sanctuary. You make sure they know: nowhere is safe. No one can protect you. Not even love.

Can you imagine? 13 years old.

What Happened to Princess Gyeonghye

The historical records go quiet about Gyeonghye after this night, which tells you everything.

She watched her younger brother lose his throne. She watched him move to Changdeokgung Palace (창덕궁) as “Sangwang” (상왕)—the retired king—which was really just a gilded cage. She watched Sejo tighten the noose.

In 1456, when the loyal ministers (the famous Sayuksin, 사육신) tried one last time to restore Danjong, they failed. They died. And Sejo had enough.

1457: Danjong was stripped of even the title “Sangwang.” Demoted to “Nosan-gun” (노산군)—just a commoner.

The day he left for Yeongwol (영월), he said goodbye to his sister one last time.

There’s a legend—not verified by official records, but passed down through generations—that Gyeonghye stood at the edge of the city, watching her brother’s exile procession disappear into the distance. She couldn’t cry. Crying would have been seen as dissent against Sejo’s order.

So she just stood there. Watching. Until he was gone.

They never saw each other again.

After Danjong’s death, Gyeonghye lived in silence. Some records suggest she spent the rest of her life in a kind of self-imposed exile, rarely leaving her home, rarely speaking about her brother. Because speaking his name—even thinking his name too loudly—could get you killed.

For 241 years, Danjong’s name was erased from official records. And Gyeonghye had to live with that erasure every single day.

Sejo’s Guilt: The Uncle Who Couldn’t Sleep

Let’s talk about Sejo for a moment, because the historical record is… complicated.

After Danjong’s death, Sejo reportedly suffered from terrible nightmares and developed a chronic skin disease that no physician could cure. There are court records of him consulting monks, shamans, and doctors—spending fortunes trying to find relief.

Some historians interpret this as psychosomatic guilt. Others say it was just coincidence.

But there’s a famous yaesa (야사, unofficial history) that’s been passed down:

Sejo would wake up in the middle of the night, screaming that he saw a young boy standing at the foot of his bed, dripping wet, eyes wide open, just… staring.

The boy never spoke. He just watched.

Sejo’s physicians documented that the king’s skin condition worsened during these episodes. His skin would break out in painful sores that looked, according to some accounts, like burns.

Modern historians are skeptical. Maybe it was eczema. Maybe it was stress. Maybe it was nothing.

But the yaesa persisted because it told an emotional truth that the official records couldn’t: You can take the throne. You can rewrite the history books. But you can’t escape what you did to a 17-year-old boy who called you uncle.

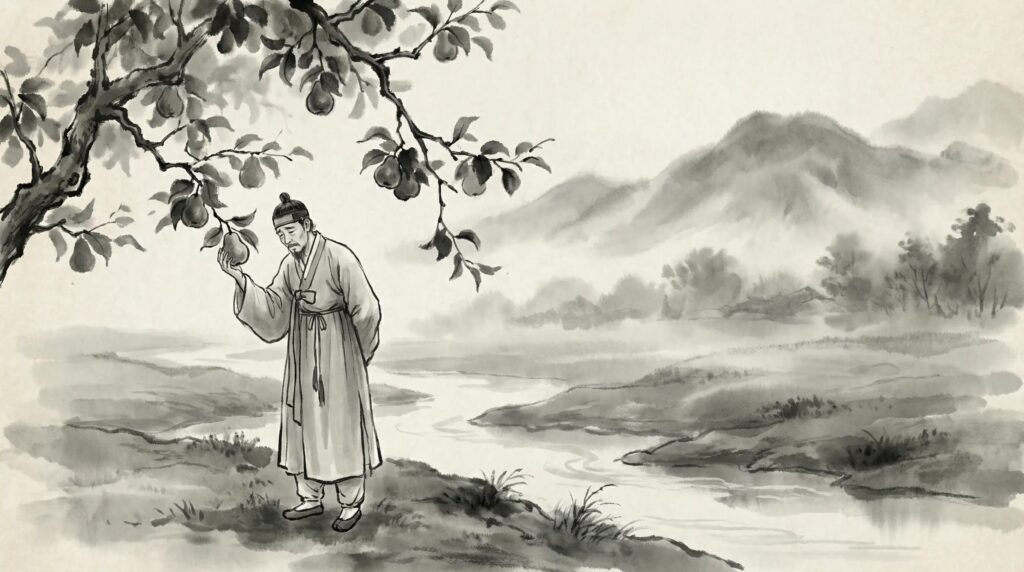

Seven Days Without Water

Summer, 1457. Danjong’s journey to exile in Yeongwol.

Seven days on the road in the middle of brutal summer heat.

The military guards escorting him? They ate full meals. They stopped at taverns to drink rice wine. They rested in the shade.

Danjong—17 years old, already weakened from months of confinement—couldn’t get a single cup of water.

Wang Bang-yeon’s Pear Trees

The escort commander, Wang Bang-yeon (왕방연), watched. He knew Danjong’s suffering. He wanted to help.

But orders are orders.

So he watched a 17-year-old boy beg for water. And did nothing.

This next part is more legend than verified fact, but it’s been passed down for 600 years, and I think there’s a reason why:

Wang Bang-yeon quit his position out of guilt. He reportedly spent the rest of his life growing pear trees (배나무) by a stream, watering them obsessively.

Every time he watered those trees—every single cup of water he poured—it must have reminded him: the water he couldn’t give.

That guilt doesn’t fade. It just grows roots. Like those pear trees.

From Si-eun to Danjong: Why Park Ji-hoon

Here’s how the casting happened, and I love this story:

Someone on Director Jang’s team told him: “You need to watch Weak Hero on Netflix.”

At the December 19th premiere, Jang explained:

“Watching Si-eun in Weak Hero, I thought: this is Danjong. I didn’t want Danjong shown as just helpless. I needed eyes that could show inner strength beneath all that suffering.”

Park Ji-hoon lost 15 kilograms for this role. His body became lighter.

But watch his eyes in that poster. They’re carrying the weight of everyone he couldn’t save.

Physically light. Spiritually crushed.

That’s the arithmetic of exile.

What We’re Waiting to See

February 4th, 2026.

This will be the first Korean film to center on King Danjong’s hidden story—not just “Korea’s saddest king,” but the brief life of a 17-year-old boy named Yi Hong-wi (이홍위).

His name means “brilliant light” (弘暐: 클 홍, 햇빛 위). He was supposed to shine like the sun over his people.

Instead, he became a boy king who lost everyone, whose eyes filled with sorrow, who met an unjust death in exile.

But he must have known how his story would end. 17 years old. Smart enough to see the trap closing.

History painted him in sorrow—a boy king drowning in grief.

Maybe this film will finally show us something more: a youth that burned briefly, but burned nonetheless.

Not just survival. Defiance in the face of the inevitable.

In that archery pose, I see what Director Jang wanted us to see: not helplessness, but a boy who chose his posture even when everything else was chosen for him.

The arrow is aimed. The form is beautiful.

That’s not tragedy. That’s dignity.

And 600 years later, we’re still watching that choice.

The King’s Warden (왕과 사는 남자) releases February 4, 2026.

Thanks for reading. I look forward to seeing you at the next one.

⛔️ Copyright Disclaimer: All drama footage, images, and references belong to their respective copyright holders, including streaming platforms and original creators. Materials are used minimally for educational criticism and analysis with no intention of copyright infringement.

🚫 Privacy Policy: This site follows standard web policies and does not directly collect personal information beyond basic analytics for content improvement. We use cookies to enhance user experience and may display advertisements.

답글 남기기