* This is the renewed version of an earlier post. You can read the original 🔗here.

“It speaks for thousands of kids who walk a line between brilliance and collapse. Weak Hero isn’t just an action drama — it’s a cautionary tale. And a call to listen before it’s too late.” — Elaine, subscriber

⚠️ A note before you read: This piece explores adolescent psychology and mental health in depth. Some themes may be difficult to sit with. Please take care of yourself as you read.

How a Drama Cured My Burnout

Around the same time Weak Hero Season 2 dropped on Netflix, I sent a half-joking message to my YouTube subscribers:

“Thanks for confirming I’m not the only one on this planet who’s completely lost their marbles over this show. We’re all in this mental institution together, bestie.”

It was a joke — until it wasn’t.

Deep down, a quiet worry had been growing. Was I spending too much time on a TV show? Were these hours on the train home — the few precious minutes I had to actually decompress from work — being wasted?

But then something unexpected happened as I started having deep conversations with fans from around the world.

A close friend of mine who works as an adolescent counsellor had actually recommended Weak Hero Class 1 when it came out three years ago. I’d completely forgotten. Teen action drama? Honestly, it didn’t exactly call my name. But when Season 2 hit Netflix, fan-made shorts and old reviews started flooding my YouTube feed — and eventually, the algorithm won. I clicked on Season 1 almost on autopilot.

One accidental click was the beginning

That one accidental click was the beginning of everything. I stayed up all night binge-watching all eight episodes, and by the end, one thought was echoing in my head:

What on earth did I watch? If I’m hooked, I’m properly hooked.

At the time, I was deep in the thick of work burnout. Every morning commute, I’d fantasise about handing in my resignation letter. “Wouldn’t it be better to just get fired?” I’d think, only half-joking. And then — right in the middle of all that — I got hit by a full-blown fandom crash with Weak Hero. What Koreans call a 덕통사고: a fandom accident.

You know how, when you’re in an accident, the first thing you do is look around for other victims? 🔗YouTube was perfect for that. I started connecting in the comments with fans who’d been willingly held hostage by this show for just as long as me — or even longer.

Seeing Su-ho through Si-eun’s eyes. Trying to understand Beom-seok’s final act on that ring — what I can only call 🔗”cinematic trauma.” I even bought the official script book and started reading it on the train home.

And somewhere in all those late-night discussions with commenters, something strange happened: my burnout started to ease.

I’d always dozed off on the train home from work. But when I’d pull out my tablet to work on a video or respond to comments, I somehow wasn’t tired at all. The passion I was pouring into this drama was coming back to me as something I can only describe as a strange kind of happiness.

To put it in Su-ho’s terms:

“Do these discussions put food on the table?”

And in Seong-je’s words, it’s the stupidly “romantic” kind of nonsense.

But while it doesn’t feed me, I’d say the romance more than passes the bar.

The Miracle of Old-School Tributes

I was honestly beginning to wonder if the production team had timed Class 2′s release to coincide with the exact period when Si-eun, Su-ho, and Beom-seok first met — late May to early June. But regardless, mid-July — the point in the Class 1 timeline when Su-ho falls into a coma — was fast approaching. I felt a growing urgency to get everything down before then. If I didn’t organise all these conversations and reflections I’d shared with fans, I feared I’d never be discharged from the ward — just like the countless “patients” who’d confessed they’d been unable to let go for three whole years.

Since the fandom accident first struck — like a fever that came out of nowhere in early summer, when I had absolutely no defences — it’s been a welcome visitor. A stupidly, ridiculously romantic couple of months.

Interpreting the work from every angle I could find. Analysing the characters. Seeing dimensions I’d missed through the eyes of commenters. I wanted to pour out everything I felt watching this masterpiece — and now I wanted to carefully preserve the conversations we’d shared. It felt like a personal duty to leave behind, somewhere, a tribute to a work that came to me almost like a saviour — the kind that destroys your daily routine so completely it saves you.

The commenters who helped build this channel alongside me — especially Elaine — embody exactly what her final words captured: this syndrome that hit like an early summer cold made me strangely happy. And I think I genuinely did experience a mild form of creative mania because of Weak Hero.

Almost like Poetry to Me

One of Elaine’s comments reads almost like poetry to me. She had discovered my YouTube channel through ChatGPT, of all things — and the depth of analysis she brings, the precision of her word choices, the way she synthesises Korean drama with a broader understanding of Asian culture, all suggest someone who has been sitting with this work for a very long time. I suspect, though I’d never ask, that she’s likely doing academic research on the Asian media industry, or Hallyu specifically. The range and depth of her perspective make that feel almost certain.

Her most recent comment ended with this:

“I’m actually trying to eke out a response to your last blog post because I think you’ve pretty much nailed it in your conclusions about Si-eun, and that makes me strangely happy. So, see you around, Jennie, and have a great weekend.”

That last line — the idea that a conclusion I’d worked my way toward about Si-eun’s character made her strangely but genuinely happy — will probably hang in my heart for a long time, like a thin thread strung between two people who’ve never met but somehow arrived at the same place.

The Romance Passed

Compared to the fast-moving, algorithm-optimized content flooding the Weak Hero corner of YouTube, my voice-driven analysis is undeniably old-school. In a world built for Shorts, not many viewers will sit through long-form content. But I knew that. I chose this anyway — the stupidly romantic method, Seong-je style. And in the end? The burnout lifted. So by those standards, the romance passed.

Creating content in English — a language that functions for me as a communication tool rather than a mother tongue — takes considerable time and effort. If revenue proportional to that investment were the goal, there are far more efficient routes. Clickbait thumbnails. Action-clip Shorts. I noticed plenty of content using Weak Hero footage in ways that, frankly, fans who genuinely care about this show would never produce. Some of the highest-view-count videos had processed scenes through AI into something almost unrecognizable — lurid, sensational — with titles including the phrase “AI ruined.” There’s a ceiling of creative integrity, and that ceiling kept me in my lane.

So what I got, in the end, was a small miracle: commenters who leave old-school tributes just as earnestly as I do somehow found this channel, and poured their time into it.

And as the fever stretched on — nearly two months of deep character analysis and careful translation, catching cultural nuances and contexts that careless subtitles on illegal streaming channels had left on the floor — international fans began to pick up on things they’d missed. The depth of what we shared in the comments only kept growing.

What Weak Hero Really Wanted to Say

Of all the comments I’ve received, the ones that stayed with me most were the ones circling a particular question: what might this work be quietly hinting at about Si-eun’s mental state?

What Director Yoo Su-min wanted to say about the character Yeon Si-eun — through the beautiful face of actor Park Ji-hoon — the meaning hidden in the space between lines, sometimes so transparently conveyed you can’t miss it. As Elaine put it: It’s a cautionary tale. One of the central stories this work may have wanted to tell — perhaps the most essential one — might be about the mental suffering teenagers carry, and how rarely anyone stops to notice it. This goes well beyond Si-eun simply being prescribed sleeping pills after losing Su-ho

This is the topic I’ve been running toward this whole time: mental health. Heavy, avoided, inconvenient — and for most people, not worth their time. Because there’s no obvious reward for sitting with it.

Of course, to tell a story this dark — boys carrying narratives almost too heavy for their age, some of them facing endings that leave cinematic trauma — a story like this needs a buffer. A neutralising element. Which is perhaps why the director borrowed the beautiful face of Park Ji-hoon, and the luminous, borderline-boyish face of Choi Hyun-wook, who at the time was standing right at the edge between adolescence and adulthood.

Director Yoo Real Courage

I believe Director Yoo showed real courage in bringing this topic to the surface — especially one that Korean society tends to turn away from even more than most. The growing pains were intense. But in that final moment, when Si-eun stands at the threshold of adulthood, Su-ho’s words — “It looks good” — carry the weight of a small, stubborn hope: that healing is possible, even within pain. That continuation is possible.

Both Directors Yoo Su-min and Han Jun-hee are fundamentally artists who understand that truth cannot surface without first touching society’s wounds. And through outstanding direction — paired with a script the fandom has described as near-genius — they succeeded in delivering a message of hope without ever forcing it.

“There are kids like Si-eun in reality. More than we’d like to think. It’s just that most of them break down in ways that are quieter and more hidden than Si-eun. What’s portrayed through Si-eun in Weak Hero is actually accurate. I suspect the director and production team did their homework.” — Elaine

Not a Diagnosis — A Closer Look

Let me be clear about something important. None of us — not my counsellor friend who recommended this drama, not the passionate commenters, not me — have any desire to slap a diagnostic label on Si-eun or pin down exactly what’s happening inside him.

This drama offered many hints about the external forces that may have shaped Si-eun, but it was carefully directed to never box the boy into a specific category. Fans are simply exploring the landscape of his inner life from different angles. Defining it precisely isn’t the point.

With that said, here is Elaine’s analysis of the scene where young Si-eun overhears his parents arguing:

“In the subtitles I saw, they were clearly arguing about whether or not they should have had him, and it was obvious both of them were regretting the decision. He had a broken arm. Dad was asking Mom where she was when it happened. She shot back that she’d agreed to have him because they were going to raise him together. And dad said he hadn’t known that the boy would get hurt so much. Little Si-eun would have been convinced that he was unwanted — a disappointing, inconvenient problem.

So he goes to his room, locks the door, and does math. Which became his way of dealing with the fact that his parents didn’t want him. He locks everyone and everything out by only doing schoolwork. And that’s what he keeps doing from then on. It’s totally a coping mechanism. If this is what he does, nobody and nothing can hurt him — and he can prove his worth to himself, and maybe to his parents and others.”

— Elaine

“But I think the implication is also that little Si-eun gets overstimulated out in the world and shuts down. He faints, falls, and since he’s small-boned and frail, he gets hurt. My biggest wonder is whether a medical team would determine he’s neurodivergent — somewhere on the autism spectrum. Isolating himself. Not communicating. Focusing his whole life on one thing.

Becoming overwhelmed by outside stimulus or internal floods of feeling. These could definitely be signs that he’s on the high-functioning end of the spectrum. Which, even undiagnosed, would have put his achievement-oriented, high-expectation parents into a state of disappointment, denial, and maybe even fear.”

— Elaine

Si-eun Coping mechanism

Many commenters have consistently pointed out that Si-eun’s obsessive immersion in math is a coping mechanism — a way to find comfort through predictability and control in an unstable world. So when young Si-eun overhears his parents essentially confessing their regret about having him, he doesn’t collapse on his bed in tears. He walks to his room, locks the door, and starts solving math problems.

The patterns commenters have identified in Si-eun are consistent: an obsessive, laser-sharp focus on academics. Childhood episodes of suddenly losing consciousness and collapsing. A pattern of social isolation, self-imposed or otherwise. Noise sensitivity — those noise-cancelling headphones he tells Su-ho he wears because “it would be annoying if people talked to me,” though it’s clear he wears them all day. A particular difficulty in regulating emotion occurs when anger builds. Extreme stress occurs when his own routines are disrupted. These are the behaviours of someone who processes the world differently.

Why Does He Get So Extremely Angry

When you first watch the drama, you get swept up in the adrenaline. This quiet boy with deer eyes and a cat-like face suddenly shows his claws. (One commenter noted that even Su-ho was sitting in the back row at that point, clearly enjoying the show — and honestly, of course he was.)

But as you watch more carefully, a sequence of meaningful questions starts to emerge: Why does he get so extremely angry? Why can’t he control it? Wasn’t his goal to get into a top university? Why would he explode so completely — risking the label of “school violence perpetrator” — when that stain could follow him for life? What does Si-eun actually want?

Compare him to Young-bin. Young-bin — for all that he is — actually has a clear reason to care about academics. He needs social validation, both for his mother’s sake and for his own self-esteem. He maintains excellent grades deliberately, with intention. (While his friends indulge in drugs at the club, he slips out to study for mock exams.)

Si-eun’s relationship with academics is entirely different. On the surface, he looks like the perfect model student — top of the class, every test paper a row of perfect circles. But unlike Young-bin, his academics don’t seem to have a clear, driving purpose. His need to excel academically is likely an inertia that formed in childhood, the natural expectation set by parents who were busy with their own careers. For a boy with his level of intelligence, maintaining excellent grades probably wasn’t particularly difficult. It was simply the most accessible way to get his existence acknowledged.

But look closely, and there’s no expectation in Si-eun — no vision of a future he’s working toward, no world beyond himself that he’s building for. He’s obsessed with the perfect circles on his test papers, yes. But he’s not building self-esteem through them, not accumulating the thrill of achievement.

As one commenter pointed out,

At some point, Si-eun seems to have given up hope of ever receiving the attention he deserved from his parents. And the consequences of that abandonment are visible everywhere — in the irregular meals, the broken sleep, the absolute social isolation throughout his school years. Not a single friend. Not a single conversation.

Can we really just say, “Top students are all like this”? Can we truly write this off as the eccentric habits of a valedictorian whose only goal is university admission?

It Speaks for Thousands of Kids

Watching Si-eun, I couldn’t help but be pulled back to my own school days. The intense stress, the narrow social circles, the English vocabulary books that never left their hands at lunch, the problem workbooks they had their faces buried in — the afterimages of friends who were entirely devoted to academics began to overlap with Si-eun naturally.

If their grades were among the top in the country, they’d have been called prodigies or geniuses — finishing school smoothly, moving on to socially respected career paths. But one particular friend’s afterimage kept lingering.

It was a conversation we never would have had if we hadn’t been assigned to the same room for a school event. It’s stayed with me to this day as a particular shade of sadness. She confessed — almost as if talking to herself — that she often thought about ways to quietly check out of this world, without pain. She too spent her days hunched over her desk just like Si-eun, right in front of the teacher’s podium. One difference: unlike Si-eun, no one ever came to disrupt her studies. Exactly as she’d always wanted.

This is exactly what Elaine’s sentence unlocked in me — the impulse to write this piece.

“It speaks for thousands of kids who walk a line between brilliance and collapse. Weak Hero isn’t just an action drama — it’s a cautionary tale. And a call to listen before it’s too late.”

Knowing that I won’t encounter another work that resonates this deeply for a very long time, I wanted to take one more step — and close out my thoughts on this masterpiece with this topic. Elaine and I shared the question: Do kids like Si-eun exist in reality? Through various conversations and research, we concluded we couldn’t look away from many children collapsing in ways far quieter and more hidden than Si-eun.

Si-eun’s Self-Harm

Setting those old memories aside and returning to the drama — I want to talk more about Si-eun’s self-harm. In my personal interpretation, even his explosive violence toward Young-bin in Episode 1 was, in its own way, a form of self-harm.

While Si-eun’s disordered eating and sleep have come up frequently in comments, what concerned me most was something else: this boy does not interact with anyone at school. Not a single friend. Headphones in all day. No conversations. At first glance, you might dismiss it as the antisocial habits of someone who refuses to waste even a minute of study time. But underneath, it’s more likely that he doesn’t want his withdrawn emotions discovered — or doesn’t want to experience the emotional overload that human interaction would bring. Based on the conversation he has with his father about fainting, I interpreted his recurring blackouts as a response to emotional overload.

And here’s what makes it worse: Si-eun carries internalised anger. When the triggers for that anger involve threats to the perfect order he obsessively maintains — or to the people he’s become attached to — that anger becomes uncontrollable. It escalates into something that is most harmful to Si-eun himself.

Notably, the drama never depicts Si-eun’s rage as heroic. It’s not like Su-ho’s action sequences, where almost perfect emotional control is maintained throughout. When Si-eun was smashing Young-bin’s face, he was retaliating like a cornered animal. Had Su-ho not stepped in at exactly the right moment, Si-eun had no rational capacity left to stop himself. He would have gone all the way. It was technically self-defence against bullying — but at a level where immediate expulsion would have been entirely justified, with every student in the class watching.

For Si-eun, that row of perfect circles on his test papers was the one thing that assured him of safety — a feeling of control in an environment that was either chaotic or impossible to govern. So when the bullies finally succeeded in breaking those circles, what followed was inevitable. His sense of control — a kind of lifeline — had been severed. And as many commenters have pointed out, Class 1 has a perfect parallel structure: Si-eun going wild in Episode 1 connects directly to him going completely ballistic in Episode 8. The triggers are different. The depth of destruction is not.

The Symmetry Between Episode 1 and Episode 8

Below is a synthesis of the in-depth conversations I had with commenters about one of this drama’s most brilliant structural choices — the way Si-eun’s explosion in Episode 1 mirrors his explosion in Episode 8, even as the triggers shift entirely.

“I completely agree that Si-eun going ballistic feels totally realistic. What makes him unbeatable at that point is the fact that he has nothing left to lose. It’s a great parallel that the first time it happened was for a similar reason — at the beginning, all he had in his life that mattered to him were academics. So when the bullies started messing with it, he lost control.”

“The parallel structure between Si-eun’s first explosion and his final one isn’t just clever writing — it feels like the emotional mathematics of a boy whose entire world gets reconstructed, and then destroyed. By the last episode, he’s lost the most important person who saved him from his self-imposed loneliness. Feeling that he lost that relationship — and feeling responsible for it — strips him of any rhyme or reason. He attacks everyone because once again, he’s lost everything that mattered to him. Except this time, it destroys him on a much deeper level.”

“Si-eun’s parents have essentially neglected and abandoned him. They expect him to be self-parenting and nearly perfect. But his father — an Olympic silver medalist in judo — has also clearly been disappointed that his son turned out frail and easily hurt. So Si-eun adapted accordingly. He became an isolated, stoic, scholastic automaton, living in an extremely rigid world where he denies his basic needs for food, sleep, and relationships.”

The Possibility of Neurodivergence

After watching this drama multiple times, I began seeing it through a particular lens: that the direction was, at least partially, hinting at Si-eun’s neurodivergence. And in some ways, I came to interpret certain elements through the possibility that Si-eun might fall somewhere on the high-functioning autism spectrum. (These are personal interpretations. The lens shifts depending on who’s watching.)

Viewed through that lens, the commenter’s observation that Si-eun and Su-ho reminded them of an autistic-ADHD friendship bond lands differently. It’s well-documented that neurodivergent individuals often feel an immediate ease with one another. Si-eun’s instant comfort around Su-ho — likely surprising even to Si-eun himself — and the way Su-ho clearly delights in Si-eun’s “weirdo” nature from the beginning, while classmates find him off-putting, start to feel not just plausible but quietly inevitable.

I’m not interested in labelling either character. What I’m interested in is the immediacy of the bond they formed, the depth of the attachment — and specifically, the higher possibility that Si-eun, more than Su-ho, may be a neurodivergent kid. And then: when his parents or surrounding adults noticed this, did they respond? Did they provide the care or support that was needed?

We already know the answer. It’s no. They likely assumed a valedictorian wouldn’t have any particular concerns. Or perhaps — if they did notice signs at some point — they denied it, brushed it aside. Maybe even used his exceptional academic performance as the rationale: “A kid who scores like that couldn’t possibly be…”

“Mom isn’t worried about her son. He manages just fine on his own.”

“There’s a lot I’m not good at.”

“Hm?”

Another Lifeline: Su-ho

And then Su-ho came — slicing through Si-eun’s walls like a knife through butter. A misdirected food delivery that suddenly threw open the door to Si-eun’s entire world. Through that accidental arrival, Si-eun experienced — in a bewilderingly short period — all the emotions he should have rightfully received from his parents: deep attachment, laughter, stability, love. They hit him like waves. Like a tsunami.

Had Su-ho not accidentally found his way to Si-eun’s door, Si-eun would never have broken out of that shell.

But — and this is worth sitting with — the range of emotions Si-eun felt toward Su-ho was so overwhelming, so wave-like in its intensity, that if these two boys existed in the real world, there might have come a point where Si-eun became dangerously overdependent on Su-ho emotionally.

There are several cuts in the direction where Si-eun’s eyes quietly follow Su-ho’s figure — the same slightly obsessive, intensely focused gaze he carries when dealing with the things he holds most precious. Like his studies. Just like those perfect circles on his test papers had functioned as a lifeline, that same perfectionist streak and laser focus that Si-eun developed for anything he started holding dear likely transferred entirely onto his new lifeline: his friend Su-ho.

Even his willingness to take beatings in Su-ho’s place, to let his own hands get bloody — that reads less like courage and more like desperation. Like a child who has barely ever experienced stability or attachment, sensing in advance that the psychological breakdown that would hit him if this precious person suddenly disappeared would be far more unbearable than any physical pain he might absorb by choice.

In other words, Si-eun’s coping mechanism — sacrificing himself to protect both the perfect circles and his friend — wasn’t healthy. Not for Si-eun. And in that context, I think it was brilliant direction that Si-eun was made to experience the trauma of losing Su-ho. Because for Si-eun to sustain his own life going forward, he couldn’t keep self-harming. That painful, necessary growth had to happen. Putting Su-ho in a coma — as sorry as I am for Su-ho, who had to spend the better part of his high school years in bed — was, dramatically speaking, exactly the right choice.

The Mental Health Story Weak Hero Really Tells

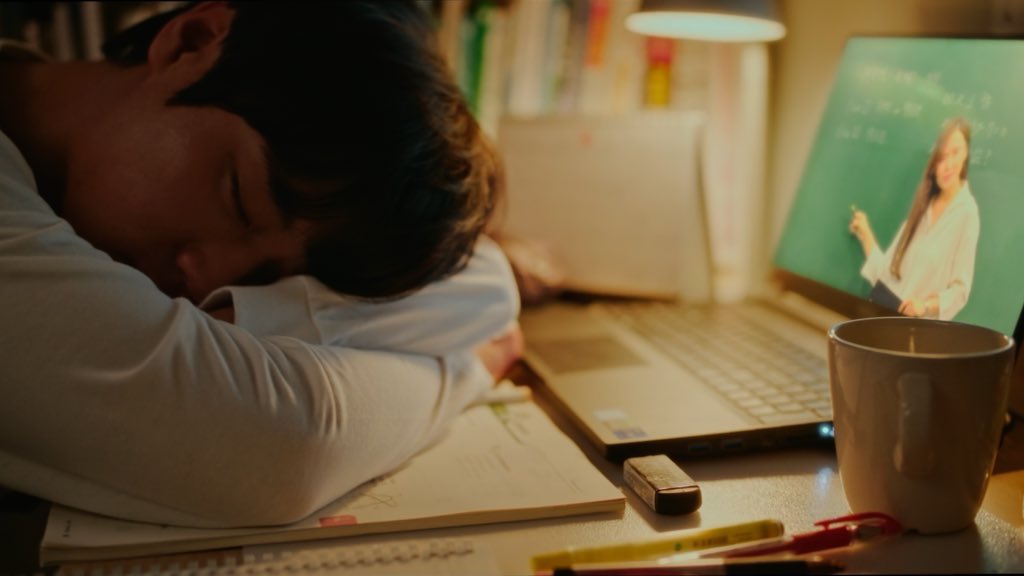

The real Si-euns who collapse in silence internally — I saw them in Season 2’s Si-eun. His insomnia had already been foreshadowed in the final episode of Season 1. Since Su-ho fell into a coma, Si-eun has been surviving hellish, sleepless nights.

His room — once warmly lit in yellow — now sits cold and muted, bathed in the weak blue light of a lamp hanging low over his desk. Even with sleeping pills, the boy can’t fall asleep until 3 AM.

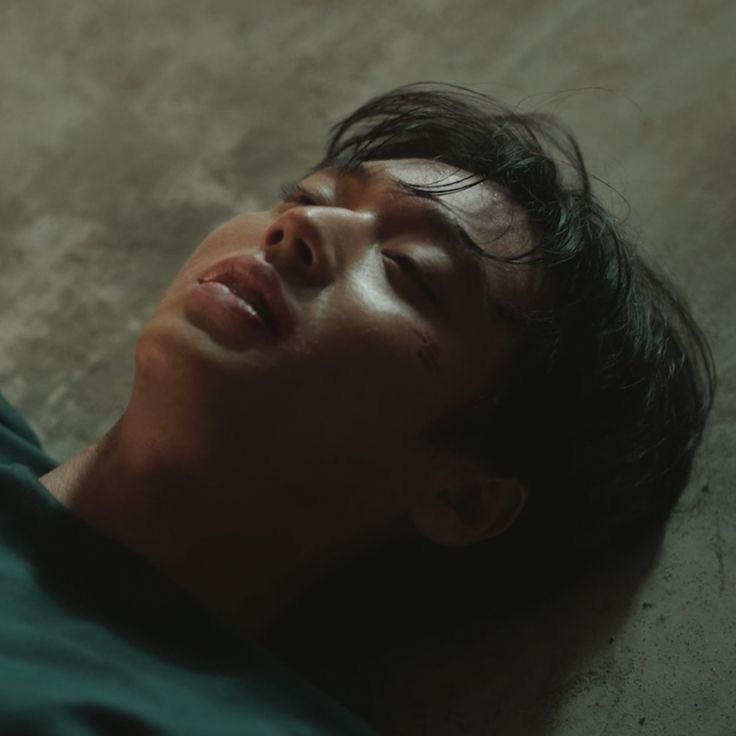

The scene of him taking prescribed sleeping pills is depicted with striking directorial clarity. And his awkward, arm-still gait — barely moving in sync with his steps — has been widely interpreted as an indirect portrayal of a boy consumed by deep depression. Many have pointed out that this disconnected way of moving is the direction’s way of signalling that his mind and body have come apart. He’s present but untethered.

“In Season 2, we see that he’s being forced to see a psychiatrist, but he won’t even talk to her because he’s so depressed and can’t see the point. He doesn’t want therapy.

He wants a different life, and his friends back — but of course, she can’t do that for him. And then there’s his flat voice and expressionless face. Not caring about much. Lack of energy. Not sleeping. Wanting to push everyone away. He’s totally self-isolating. And self-blaming.

All kinds of cognitive distortions. Not even a doctor could fully diagnose someone like Si-eun without a thorough, accurate history — but it’s pretty hard not to look on and conclude that Si-eun is no stranger to depression. Probably an ongoing clinical depression that’s been going on for years. And then it gets worse before it gets better.”

— Elaine

Loss, Healing, and Growth: The Eunjang Chapter

After completely falling apart in Class 1 — with no school willing to take him, barely escaping juvenile detention — Si-eun was sent to Eunjang High. And it was there that something shifted. He met Ba-ku, Go-tak, and Jun-tae. Their friendship — not too close, not too distant, with a sustainable rhythm he’d never had before — gave him something entirely new to look toward.

His decision to release Beom-seok’s hand on that ring — the act that had been feeding his hellish sleepless nights — was symbolic. It represented his choice to free himself from the guilt he’d been holding onto, and his determination to heal and grow despite his losses.

The drama never spells it out. But anyone who truly understands this show can feel it: Si-eun was slowly, carefully breaking free from the shadows of the deep psychological struggles that had been weighing him down. We see his depression starting to lift when he’s able to build meaningful relationships with people who accept him as he is — without demanding perfection. And if he can maintain that kind of connection, with people who will actually stay — then maybe, bit by bit, he moves closer to simply being himself. An ordinary introvert.

The massive psychological breakdown Si-eun went through as the price of losing Su-ho wasn’t simply a tragedy. It was the growth he had to go through. Like a bird breaking out of its shell — you can’t survive just by cracking open. Si-eun had to learn to live without his coping mechanisms — without the perfect test scores and Su-ho as his twin lifelines — to genuinely grow into an adult.

If he had kept trying to protect those lifelines by scarring his own body and shedding blood, he never could have grown properly. And the people who care about Si-eun wouldn’t have wanted him to keep hurting himself either.

So when Su-ho finally woke from his long sleep and saw Si-eun running over — with friends, this time — and chose to say “It looks good” out of everything he could have said, those words carry real weight. He was genuinely proud of Si-eun’s growth. Celebrating a bird that had learned to fly on its own. Su-ho’s original line, apparently, was meant to be:

“Our Si-eun has really grown up.”

Do the Real Si-euns Have Their Su-ho?

We see that Si-eun has grown enough to convince himself that he can build a sustainable life with his new friends. But the question stays.

Do the real Si-euns — the ones out there right now — have Su-ho-like figures in their lives? Someone who will show up, look them in the eye, and say:

“Have you been living okay?” or “It looks good”?

Some children collapse silently. Developing depression, anxiety, suicidal thoughts — with no visible cracks on the surface. Others explode when a crisis finally arrives, lashing out violently or breaking down emotionally. And most of the time, the adults around them had no idea what was building underneath.

If this drama has brought us to a place where we’re asking these questions — where fans from across the world are sitting with the weight of Si-eun’s story and asking “Do kids like this exist in reality?” — then Weak Hero has succeeded in doing something far beyond what a school action drama is supposed to do. And it did so through precision: a meticulously adapted script, sophisticated direction, and a performance from Park Ji-hoon that externalised an interior struggle through nothing more than a blank face, a flat voice, a swollen face from sleepless nights, and an awkward, disconnected walk.

It’s no exaggeration to say I spent these two months caught in a fever like an early summer cold — and I don’t regret a single moment of it. Getting to have these high-level discussions with fans from all over the world, freely and joyfully — that alone made it worth everything.

In Seong-je’s terms, stupidly, recklessly romantic. But strangely, deeply happy.

his piece is my final small tribute to Weak Hero.

Thank you for listening.

Additional Info

📍 This post is part of an upcoming free e-book — a small thank-you to everyone who’s been part of these conversations. If you’d like to receive it when it drops, make sure you’re subscribed to my Beehiiv newsletter. All work is expected to be completed within the next month. See you there.

Also,

Want to keep up with the latest on our canoe trio — Ji-hoon, Hong-kyung, and Hyun-wook — plus their projects and all things K-drama? Subscribe here:

Read More: Weak Hero isn’t just an action drama; It’s a cautionary tale — Renewed Version

- Weak Hero isn’t just an action drama; It’s a cautionary tale — Renewed Version

- This Is How Choi Hyun-wook Shows Up | Curtain Up, Class! Teaser Review

- Your Reactions to The King’s Warden: From Wet Raft Scenes to Hamster Cheeks

- The King’s Warden: Hidden Details You Completely Missed

- THE KING’S WARDEN Opening Day Review: Worth It?

📢 Personal interpretation notice: All content in this piece is based on the personal interpretations and analysis of a fan. It does not represent the official position or intent of the production team. This was written purely from a fan’s perspective, for discussion and reflection.

⛔️ Copyright: All drama footage, images, and references belong to their respective copyright holders, including streaming platforms and original creators. Materials are referenced minimally for educational criticism and analysis. No copyright infringement is intended.

🚫 Privacy Policy: This site follows standard web policies and does not directly collect personal information beyond basic analytics for content improvement. We use cookies to enhance user experience and may display advertisements.