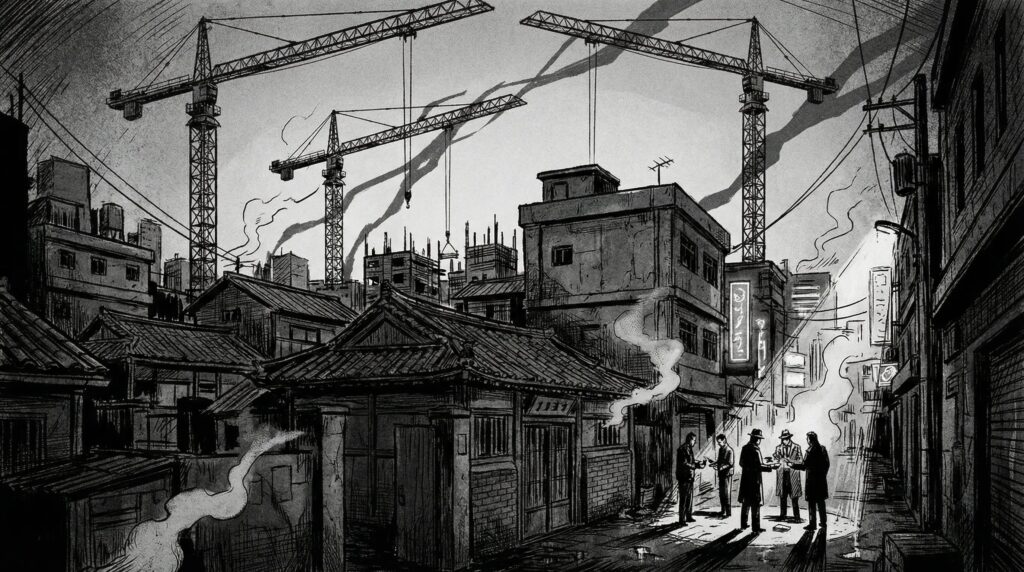

There’s a moment in Made in Korea that I can’t shake.

Two men on a rooftop in Busan. The air thick with tension. One lunges forward—fist clenched, rage barely contained—ready to send the other tumbling into the abyss below.

But the punch never lands.

Not because of mercy. Because of the calculation.

That’s when I knew: this drama understands something fundamental about power, about ambition, about the lies we tell ourselves to justify the terrible things we do.

And at the center of it all stands Baek Gi-tae—polite, meticulous, and utterly terrifying.

Let me tell you why I couldn’t stop thinking about him.

The Rooftop

The rooftop in Busan. Two men, face to face.

Baek Gi-tae lunges forward with the fury of a man about to smash his fist into Pyo Hak-su’s face and send him tumbling off the edge.

But his fist never lands.

Not because he’s merciful, but because he’s already three moves ahead.

He knows Hak-su is a spy planted by the presidential security chief—the very pinnacle of Korea’s power structure—and he’s already calculating how to turn that fact into leverage.

So he just growls. A warning. A performance.

Everything is transactional in this world—every glance, every word, every gesture calculated for maximum advantage.

These men’s minds never stop churning until sleep finally shuts them down.

For this role, Hyun Bin gained over ten kilograms, and you can feel that weight pressing against the screen—a physical manifestation of ambition turned flesh.

And Noh Jae-won, playing the much younger Pyo Hak-su, looks him dead in the eye and teases: “Turns out this guy’s a fox.”

He never loses an inch in this power game.

This tension. This coiled, dangerous energy.

This is where we begin.

Woo Min-ho’s Signature

Dir. Woo Min-ho. If you know the name, you know what’s coming.

If Made in Korea is your introduction to his work, I urge you—no, I beg you—to seek out his earlier films: The Insiders and The Man Standing Next.

Because Woo Min-ho has made a career out of understanding one thing better than almost anyone else in Korean cinema: what men want, and what they’ll do to get it.

He excels at depicting men’s raw ambitions—not the sanitized, Hollywood version of ambition, but the ugly, desperate, all-consuming kind.

How those desires collide like sparks thrown against gasoline, igniting and escalating toward a climax where someone—inevitably, tragically—has to die.

There’s a scene in The Insiders that lives rent-free in my head.

Prosecutor Woo Jang-hoon and gangster Ahn Sang-goo by the river, laying bare each other’s desires with a brutal honesty that feels almost obscene.

Prosecutor Woo—no prestigious law school degree, no family connections, no political godfather—craves advancement in the organization with a hunger that borders on desperation.

Gangster Ahn dreams of revenge with the single-minded focus of a man who has nothing left to lose.

They verbally expose each other’s ambitions without shame, without pretense, and these two men whose desires have been stripped naked brazenly confront one another.

It’s the most tension-filled yet strangely cathartic climax in The Insiders.

In Made in Korea, this eruption of desire is expressed even more stylishly, more sophisticatedly, more dangerously.

I watched these scenes and thought: this is a director who has reached the apex of his craft.

The Fox

Baek Gi-tae, played with unsettling precision by Hyun Bin.

Did you find him compelling? I did. And I suspect you’re not alone.

Because beyond the sharp suits and the movie-star face, we glimpse something uncomfortably familiar in Gi-tae’s eyes—something of ourselves, perhaps, or of people we know.

First: Honest Ambition

Gi-tae harbors a dangerous yet audacious goal: to stand at the pinnacle of living power—not inherited wealth, not the fading glory of old families, but real, tangible, unchallengeable power.

Even the presidential security chief—Korea’s power apex, the man who literally guards the president’s life—can see that ambition radiating from Gi-tae like heat from asphalt in August.

As Prosecutor Jang Geon-young observes, Gi-tae is extremely polite and proper on the surface.

But underneath? Underneath hides a ferocity that could tear through steel.

A Janus-faced man. Two souls in one body.

Second: The Need for Justification

And here’s where it gets interesting—and disturbing.

Gi-tae isn’t a character completely stripped of humanity, a hollow shell going through the motions of being human.

In fact, no one in this drama is portrayed that way.

Even Director Hwang, who pulls the trigger on people’s heads with the casual ease of someone turning off a light switch, asks his subordinates: “Have you ever experienced real love?”

That question tells you everything: he has. He knows what it feels like.

And in episode three, when Jo Yeo-jeong’s Bae Geum-ji—a character who carved herself into the drama’s DNA with a scalpel—stirs up high-ranking officials like a hurricane through a house of cards, Director Hwang sees through to her core: “She actually just wants to be loved.”

So every character in this drama is a Janus figure, carrying contradictions like precious cargo.

No one is drawn as a soulless psychopath. And Gi-tae is no exception.

But here’s what fascinated me, what kept me up at night turning it over in my mind: Gi-tae justifies his drug business as “patriotism.”

Even as he drags his younger sister So-young into the trade—his own blood, his own family—he tells her with absolute conviction: “This is patriotic.”

Watch his eyes when he says it. Watch the earnestness in his tone.

He genuinely believes it. This isn’t just a convenient lie, a flimsy rationalization to help him sleep at night.

It goes deeper—much deeper—than guilt management.

He has convinced himself that distributing drugs to Japan and earning foreign currency is an act of patriotism.

His refusal to distribute in Korea? That’s proof, in his mind, that he’s protecting his country.

“I won’t poison my own people. Only the Japanese. Only the enemy.”

The mental gymnastics required for this level of self-deception would win an Olympic gold medal.

Third: Blood Loyalty

There’s a scene in Osaka, in a modest Korean restaurant, where Choi Yoo-ji says something that cuts to the bone: “What’s with this obsession over blood ties?”

Listening to Yoo-ji, Gi-tae resonates deeply. He gets it. He feels it.

He cherishes his younger sister, yes, but especially his much younger brother Gi-hyun—a boy he raised more like a son than a sibling.

His power hunger, his ruthless climb, his willingness to do terrible things—part of it, perhaps most of it, is for them.

Even if everyone in the world betrays him, backstabs him, uses him and discards him, he holds one unshakeable belief: his blood relatives won’t.

In 1970s Korea, this wasn’t unusual. Many families lost parents early during the Korean War, leaving eldest sons to become surrogate fathers to siblings with large age gaps.

That’s the context Gi-tae was born into. That’s the world that shaped him.

So we can’t simply call him evil—though evil things he certainly does.

Instead, we become absorbed in this Janus-faced man riddled with contradictions: his brutal honesty, his self-serving rationalization, his capacity for violence, and yet—and yet—his almost tender devotion to his bloodline.

A Lineage of Ambitious Men

Dir. Woo Min-ho excels at portraying these multifaceted male characters, men who are honest about their desires in ways that make us uncomfortable precisely because we recognise the impulse.

Let me walk you through his lineage of ambitious men.

The Insiders: Prosecutor Woo Jang-hoon

A former detective turned prosecutor. No Seoul National University law degree. No family connections in the prosecutor’s office. No inherited wealth or political backing.

But he’s desperately, hungrily focused on advancement—not because he’s greedy, but because he knows the alternative is being crushed.

He knows that to survive in an organization that values connections over merit, he’ll have to do dirty work.

Yet fundamentally, at his core, he’s righteous. He believes in justice.

But—and this is crucial—being righteous doesn’t mean he doesn’t want to climb the ladder, doesn’t mean he’s content to remain powerless.

He clearly wants to matter within the organization.

He wants his voice to count for something.

The Man Standing Next: Kim Gyu-pyeong

The president’s closest aide, the ultimate second-in-command, the man who stands next to power.

But he’s a man whose entire soul is being consumed, slowly, inexorably, by the president’s push-and-pull, the constant psychological torture of being told he’s indispensable while simultaneously being reminded he’s replaceable.

He ultimately withers under this treatment, like a plant denied sunlight.

He’s by the president’s side, physically close enough to touch, but he knows the real power isn’t in his hands.

He knows that power is a mirage, a shimmer in the desert that disappears the moment you reach for it, dispersing with one press of the president’s finger like smoke.

“You have me by your side.”

The president says this like it means something.

With this one line, the number one deflects everything—all responsibility, all accountability, all consequences.

Beneath him, Kim handles all the dirty work birthed by his superior’s desires, only to be discarded when the cost becomes too high.

And in the end, he impulsively enacts deadly revenge on his boss—a desperate, futile act that destroys him as surely as it destroys his target.

He too is a man honest about his desires, even if that honesty comes too late.

Made in Korea: The Complete Form

And then we come to Gi-tae.

Not phantom power that exists only in title.

Not easily replaceable advancement that can be stripped away with a phone call.

But real, tangible, living power—the kind that doesn’t evaporate when the political winds shift.

To seize that kind of power, Gi-tae knows he needs not just promotion, not just a title, but inexhaustible money.

Money is the root that anchors power to reality.

He’s a dangerous yet cunning fox-like man who understands the game at a level his predecessors never quite grasped.

So watching Gi-tae felt like watching an upgraded version of Woo’s previous characters—the complete form, the final evolution.

A man who starts as a KCIA section chief and aims to reach not just the apex of the organization, but the apex of actual power in the nation.

When Foxes Collide

But here’s the problem with a world full of ambitious men: their desires don’t exist in isolation.

When Gi-tae’s desire collides with other Gi-taes’—other men who want the same summit, the same throne, the same untouchable position—they ignite and erupt like gasoline meeting flame.

They check each other. Read each other. Calculate and recalculate.

They fight.

This is the world of men that Director Woo draws with such unflinching clarity: a brutal world of power where survival depends on being smarter, faster, more ruthless than everyone else racing toward the same summit.

In a fight where it’s either you or me, someone must fall. Someone must be destroyed.

There’s no middle ground, no compromise, no shared victory.

It’s a zero-sum game played for the highest stakes imaginable.

And perhaps most tragically: it’s a world where yesterday’s enemy can become today’s ally, and today’s ally tomorrow’s corpse.

The only constant is the hunger. The endless, gnawing hunger for more.

“This Is Patriotic”

But this justification of “patriotism” that Gi-tae uses—this linguistic sleight of hand, this moral contortion—didn’t emerge from nowhere.

In the 1970s in Korea, this actually worked. This was real. This happened.

Back then, Korean drug manufacturers would sell methamphetamine to Japan while brazenly, publicly declaring: “We’re rotting the minds of the Japanese and earning dollars. That’s patriotism.”

Read that again. Let it sink in.

They said it out loud. They believed it. Or at least, they convinced themselves they believed it.

This was an era obsessed—no, possessed—by economic development and exports under the national slogan “Let’s Live Well.”

A time when selling anything, absolutely anything, for money made you not just acceptable, but laudable. A patriot. A contributor to the nation’s rise.

It didn’t matter what you sold. Weapons? Fine. Textiles? Great. Drugs? Well, if it brings in foreign currency…

The mental gymnastics here are Olympic-level, but they made a sick kind of sense in the context of post-war Korea, a nation traumatized and humiliated by colonization, desperate to prove its worth, desperate to never be weak again.

“We won’t poison our own people. Only the Japanese. Only the colonisers. Only those who hurt us.”

The revenge fantasy wrapped in economic pragmatism wrapped in nationalistic fervor.

A matryoshka doll of justifications, each one uglier than the last.

And that distorted self-portrait of the era—that twisted mirror reflecting Korea’s rapid, ruthless, anything-goes economic rise—that’s what created the monster called Baek Gi-tae.

He’s not an aberration. He’s a product. A logical outcome.

He’s what happens when a nation decides that the only thing that matters is winning, and everything—ethics, morality, human decency—is negotiable in service of that goal.

The Question

Gi-tae is a man who aims beyond just surviving this system.

He wants to become Korea’s real living power—not a cog in the machine, but the hand that turns the wheel.

For that, he needed this era backdrop shadowed by chaos and disorder, this moment when everything solid was melting into air, when the old rules were breaking and new ones hadn’t yet been written.

But here’s the question I keep turning over in my mind, the one that won’t let me sleep:

Is this portrait only from back then, the 1970s?

Or do we still live in a world where ambition justifies cruelty, where economic success excuses moral failure, where “for the nation” can be used to rationalise almost anything?

I don’t have an answer. I’m not sure anyone does.

But I know this: Made in Korea isn’t just a period drama about the past.

It’s a mirror held up to our present, asking us to look—really look—at what we’ve become, at what we’re willing to overlook in the name of success, at the monsters we create and the ones we might become.

Made in Korea is now streaming on Disney+.

Watch it. Think about it. Let it disturb you.

And then come back here and tell me what you saw in Baek Gi-tae’s eyes.

Because I’m still trying to figure it out.

Want to go deeper? This is just the beginning of our conversation about Made in Korea. Here on the blog, I explore the cultural contexts, historical realities, and linguistic nuances that transform how we understand these stories—a space where analysis meets reflection, where Korean drama becomes a lens for understanding culture, history, and ourselves.

Join me in this space between worlds.

See you in the comments.

—Jennie

⛔️ Copyright Disclaimer: All drama footage, images, and references belong to their respective copyright holders, including streaming platforms and original creators. Materials are used minimally for educational criticism and analysis with no intention of copyright infringement.

🚫 Privacy Policy: This site follows standard web policies and does not directly collect personal information beyond basic analytics for content improvement. We use cookies to enhance user experience and may display advertisements.